I due Foscari - The Two Foscari

1843 was just one year after Verdi’s huge success with Nabucco. He was in an incredible flow. Not only because he was sought after from every corner of Italy… But also as he was composing a lot, with new ideas on a daily basis, and projects running parallel side by side. He had one well-received opera after Nabucco, I Lombardi alla Prima Crociata -The Lombards on the First Crusade, and now he needed new stories to put to music.

In 1843 he was negotiating with Teatro La Fenice in Venice to make an opera within the Venetian framework. Verdi wanted to use Lord Byron’s I due Foscari, but as it pictures Venetian politics in a rather bad light, the Venetian Theater wouldn’t risk it.

When he was approached by Teatro Argentina in Rome, he imagined making an opera about the Medici family from Florence, especially about Lorenzino de’Medici. Lorenzino is famous for having killed his cousin Alessandro and by doing so, liberating Florens from a tyrant. But killing off Kings and Dukes on stage was not appreciated by the Roman police.

So Verdi just changed the subjects and suggested his Venetian play to the Romans. And that solved the censorship problems. For the Venetians, he wrote Ernani, based on the novel by Victor Hugo. And that story is set in Spain so the Venetian censors didn’t have any objections.

Premiere – November 3, 1844, Teatro Argentina, Rome, Italy.

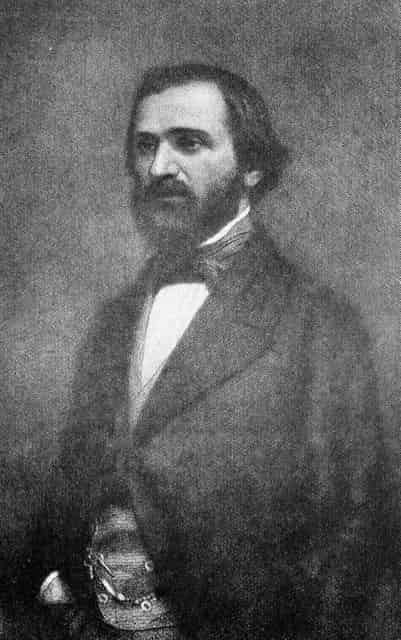

Composer – Giuseppe Verdi

Librettist – Francesco Maria Piave

Running Time – 2 hours, plus Intervals.

Three Acts

Ouverture – 3 minutes

First Act: ca 40 minutes

Second Act ca 40 minutes

Third Act ca 34 minutes

In Italian

Main characters

Francesco Foscari – Lyric-Dramatic Baritone. Doge of Venice.

Jacopo Foscari – Lyric Tenor. Francesco’s son.

Lucrezia Contarini – Lyric-Dramatic Soprano (Dramatic Soprano with agility). Jacopo’s wife.

Jacopo Loredano – Bass. Member of the Council of Ten. An enemy of the Foscari family.

Barbarigo – Tenor. Senator.

Pisana – Mezzo-soprano. Lucrezia’s friend.

Download this short Pdf-guide. Print it, fold it, and keep it in your pocket as a help when you’re at the Opera. Please keep your phone turned off when inside the theater.

Background – The opera I due Foscari is set in…

Venice

The time is 1456 – 1457.

I due Foscari revolves around the political system of the Republic of Venice… And that is a very complex argument. More about that here.

The Republic of Venice existed from 697 till 1797. At the time of Doge Francesco Foscari, the Republic was at the peak of its power holding most of northern Italy, the whole eastern Adriatic Sea coast, and practically controlling the whole eastern Mediterranean. It was a European superpower. But if you’re at the top, the only way to go is…

After decades of wars, the disasters abroad culminated in the Ottomans conquering Constantinople in 1453. And in Venice, political adversaries piled up against Francesco and his family.

Because the Doge title wasn’t like most of the medieval princes and kings at the time, hereditary. The Doge in Venice was an elected figure. And to limit his powers, he had many rules, groups, councils, and advisers to reckon with.

Because the Doge title wasn’t like most of the medieval princes and kings at the time, hereditary. The Doge in Venice was an elected figure. And to limit his powers, he had many rules, groups, councils, and advisers to reckon with.

The Council of Ten was a sort of state police. Ten senators elected from the Great Council formed a group to fight off any attack on the Republic. With time the Council of Ten became very powerful, including both political and justitial powers. The events laid out in Verdi’s opera are some facts that led to the Great Council from 1468 strongly limiting the authority of the Ten.

I due Foscari as a political statement.

Verdi was not only a famous composer but also kind of a gathering force for the nationalistic movement of the time. In the summer of 1844, he declared that he just couldn’t continue working with the opera. He had something of a writer’s cramp. The reason for this was without any doubt the situation in Italy in general, and the execution of the Bandiera brothers in particular.

Although he continued and finished the opera in time, it is very easy to notice how he portrays the Ten, and how they execute their power. One of the main themes of the story is how Francesco puts his responsibilities to the Republic (… the law) before his responsibilities to his family (… Jacopo). He feels his hands are tied.

Plot

Overture

First Act – Part One.

The Ducal Palace in Venice.

The opera opens with the Senators (chorus) waiting for the assembly to open. Interestingly Verdi has them singing very softly.

– Silent… Mystery… He keeps constant vigil, Marco the Lion.

Verdi has them sing short separated notes in a very soft voice with occasional outbursts. More than a council the music gives the impression of a shadowy organization.

Jacopo enters and alone he sings:

– Dal più remoto esilio…

He is back in Venice after a long exile, and now he’s accused once again of a crime he didn’t commit. He awaits the council’s decision. He could be facing execution.

First Act – Part Two.

Palazzo Foscari, The Foscary family’s residence.

Lucrezia too is awaiting the result of the assembly.

It is interesting to hear how Verdi portrays her. First, listen to the “Leitmotif”, the musical theme that follows her through the opera. These are the first bars of the scene. Then notice how strong and demanding she is, when she exclaims:

– No… mi lasciate… andar io voglio a lui…

She is the most heroic of all the three main characters. Compare this with Fidelio by Beethoven.

She desires to ask her father-in-law, the Doge, to have mercy on his own son. She is talked out of it by her handmaids. But when Pisana enters and reveals that Jacopo has been shown “mercy”… Instead of death, he’s been sentenced to continued exile, she explodes in fury at the Nobils of Venice:

– La clemenza?… s’aggiunge lo scherno! (Mercy?… Now you add mockery? O patricians… tremble! Your works are measured from heaven…)

First Act – Part Three.

Back in The Ducal Palace.

The Senators (chorus) praise the Venetian justice. Strong enough to sentence even the son of a Doge.

First Act – Part Four.

The Doge’s private chamber.

Alone Francesco sings about his cruel fate. Forced to condemn his own son.

– O vecchio cor, che batti…

Lucrezia enters, and one of the highlights of the opera begins. This is a beautiful scene between the two, the father and his stepdaughter. She opens up with strong accusations against the Ten, but Francesco reminds her where she is and who she’s talking to. But unlike any other docile lady in the Republic, she defies him:

– But you were there… You sat among them as a judge…

So, he shows her a note written by Jacopo admitting to the crimes. But she counters the evident proof…

– But he wrote that only to save his life…

After having tried to explain how broken his heart is, the Doge of the Republic finally has to admit that he can’t save him. With an outcry in F minor, he sings:

– No di Venezia il principe

in ciò poter non ha! (No, in Venice the Prince has no authority in this!)

This is possibly a way for Verdi to relieve pressure on the top authority and to put the blame at a lower level. A politically tactical step, and one that sits well with the poor and hungry as well as with the Kings and Dukes.

They finish the act with a beautiful duet. Francesco in despair, and Lucrezia praying for her husband.

Second Act – Part One.

The state prison.

Jacopo alone. He is delirious. He sees the ghost of The Duke of Carmagnol who seemingly accuses him of being sentenced to death by his own father.

The Duke of Carmagnol was a mercenary captain. He was famously and supposedly executed on false evidence. This happened in 1432 and it was done by the Council of the Ten.

He sings:

– Non maledirmi o prode…

Now Lucrezia enters. She tells him that no, he’s not going to die. But he’ll be sent into exile again. Together they sing about their love and their cruel fate.

The scene is interrupted by the Gondoliers (chorus from off-stage) singing a very typical Venetian barcharole. The barcarole returns at the beginning of the third act.

Verdi probably felt the second act as being a bit too negative. More or less everybody’s crying. The contrast between the Gondoliers’ song and the gloomy atmosphere inside the prison is funny.

Francesco enters and all three sing together about the hope they have to be able to see each other again:

– Nel tuo paterno amplesso…

When Jacopo cries out:

– Who will help me?

Loredano’s voice is heard from the shadows:

– I will.

It’s a cruel joke that lets Verdi show how truly evil he is.

In a last desperate outcry, Lucrezia says:

– I will go too…

But the council will not allow it. For himself, Loredano whispers:

– Wicked race (… the Foscari), fatal to my blood… The fatal hour has finally arrived, so longed for by me.

Second Act – Part Two

Inside the Chamber of the Council of Ten.

The second act finishes with a big scene, in which everybody takes part. First, we see the Council of the Ten and other senators. After a short chorus, Francesco enters. He sits on the throne but with a heavy heart. It is obvious that here he must act as the Doge of Venice, not as a father.

Jacopo is called and when he reads the sentence he calls for help from his father.

– Father, have you nothing to say for your outcast Jacopo?

But Francesco will not plea for his son.

And now Lucrezia and her children enter the chamber to which entrance is restricted to counselors. And she is strong enough to do what the Doge is incapable of. She begs…

– If you ever felt the affection of being a father or a son let it move you to pity.

But the council is not moved by tears or beggings. The law stands and Jacopo is sent to exile., and Lucrezia and the children are forbidden to follow.

Third Act – First part.

Saint Mark’s Square.

It’s the day of the regata. Everybody’s in the square. The chorus repeats the barcarole from the previous act.

– Tace il vento, è quieta l’onda. Mite un’aura l’accarezza…

There should be a ballet on stage. The crowd moves out of the way, as they are afraid of the representatives of the state (Loredano). Barbarigo says:

– There’s no need to be afraid…

But Loredano whispers to him:

– These people are cowards…

Jacopo is on his way to the Galley accompanied by Lucrezia and Pisana. We hear it from his theme in a solo clarinet. He weeps:

– Away from you, living means only death…

He boards the ship.

Third Act – Second part.

The Doge’s private chamber.

Francesco is grief-stricken and he can’t rid himself of his guilt. He sings a short aria:

– Egli ora parte!…

Now, in just a few minutes a lot happens:

- Barbarigo, a member of the Council, arrives with a message. A certain Donato before his death admitted to having committed the crime for which Jacopo was incriminated. That means that Francesco’s son is a free man.

- Then Lucrezia enters and tells him that Jacopo has died from a broken heart.

- After that, the Council of Ten arrives to ask Francesco to give up his position as Doge due to his high age.

So, at first, the Doge refuses:

– Already twice I have tried to abdicate but you wouldn’t let me…

They answer:

– You will enjoy peace among your loved ones…

To which Francesco shouts:

– … Then give me back my son!

In the end, he gives in and abdicates. But when Lucrezia arrives to salute him, he hears the bells of San Marco on the square pronouncing that a new Doge already has been elected. They have already chosen Pasquale Malipiero as his successor.

He has lost everything and dies in the arms of Lucrezia from a broken heart.

Things to look out for.

First Act

- Curtain up – Silent… Mystery… Listen to how the senators are characterized.

- 4 minutes – Dal più remoto esilio… Jacopo’s first entrance. Listen to his very own musical theme when he enters.

- 10 minutes – Lucrezias theme when she enters.

- 14 minutes – Tu al cui sguardo onnipossente. Lucrezia’s first aria.

- 22 minutes – Francesco’s theme initiates the 3rd scene.

- 24 minutes – O vecchio cor, che batti… Francesco’s solo scene.

- 34 minutes – No di Venezia il principe

in ciò poter non ha! Francesco reaises his voice.

Second Act

- Introduction with a solo viola and a solo cello.

- 13 minutes – Right after the barcarole off-stage Jacopo sighs: There you laugh, here you die…

- 23 minutes – Loredano enters the prison to mock his adversaries.

- 30 minutes – Francesco enters the council.

- 32 minutes – Jacopo enters. Check how many times the Doge denies to plea for his son.

Third Act

- 2 minutes – The ballet.

- 6 minutes – Donna infelice… Jacopo and Lucrezia start their farewell scene.

- 16 minutes – Barbarigo tells the Doge that Jacopo is free. Then Lucrezia tells him he’s dead.

- 18 minutes – Più non vive. Lucrezia’s aria.

- 23 minutes – The Ten come to ask Francesco to abdicate.

- 30 minutes – The bell from Saint Mark’s bell tower is heard.

I due Foscari – The Two Foscari. Verdi’s most boring opera.

If you just sit down and watch it, it is boring. Byron’s book is very stationary and all the development is within the characters, their inner dialogue. So, when Francesco Maria Piave got his hands on the book, he could do only so much. Nothing really happens throughout the whole story.

But that’s not the way you should watch it… Or more precisely listen to it. Because if you study the story, the music, and something about what was going on in Italy at the time, you will penetrate into a fascinating world of outspoken and not-so-outspoken defiance against the ruling class, and the oppression, domestic, and foreign, that Italy faced during those years.

Verdi introduced revolutionary ideas into the music, that could never have been put into words. His opera is much more revolutionary than what the libretto by Francesco Maria Piave suggests. In fact, in Naples, the capital of the Kingdom of the two Sicilies, this opera was by far the most popular and most played of Verdi’s operas until after the unification of Italy at the beginning of the 1860s.

In this article, I have put down my thoughts about it. But please check out the history of Italy and Europe from other sources. Much of modern Europe (… and much of the Americas as well,) was founded in those decades in the middle of 1800, when industrialism swept over the Western world, national states were born, and borders were drawn.

The complex voting system of the Republic.

Venice was not a kingdom. It was a political system based on elected councils… A sort of democracy if you want. But it had nothing to do with the modern-day democracies. Only the nobles could vote, not the average citizen. And to defend the election system against forces within the state that would rather have a hereditary monarchy, an immensely complicated system of voting was created. And during the centuries, it was made even more intricate…

The Great Council was sort of a parliament, where all the noble families of the Republic were represented. It consisted of more than a thousand members, and their most important task was to choose a Doge. And that’s where the fun begins:

First, they excluded everybody who wasn’t 30 years of age. Then 30 of these were extracted by lottery, and the youngest of the chosen group walked over to the Basilica next door to pray. On his way back he picked up a random, young boy between 8 and 10 years of age. That boy would then be the conductor of the whole process:

The boy would then again draw the 30 ballots but this time only 9 of them contained a name. These nine counselors went into another room and elected 40 names. These 40 were then reduced to 12 by another lottery. These 12 had to elect 25 members, from which 9 were extracted who would then elect 45 councilors, from which to extract 11 who would finally appoint 41 counselors.

This last group went to mass, made their confession, and after more prayers, these 41 counselors elected the new Doge. The random boy from outside the Palace was the one responsible for counting the votes and distributing the ballots.

To cast the vote, the counselor held a small ball made of fabrics (… to not make a sound when falling) in his closed fist, which he then put inside a big urn. There he opened his hand and let the ball fall. A small ball in Venetian is called Ballotta, and this term gave name to the English word ballot.

This was a very complex way to choose a leader. Still, it was in force roughly in the same way for more than 500 years. Not many political systems of today can beat that.

Download this short Pdf-guide. Print it, fold it, and keep it in your pocket as a help when you’re at the Opera. Please keep your phone turned off when inside the theater.