Il Trovatore - The Troubadour

La Trilogia Popolare – The Popular Trilogy.

Together with Rigoletto, and La Traviata, Il Trovatore is part of what is called La Trilogia Popolare. Verdi never labeled them that, and he never intended them to be lumped together. They are three works that are not connected in any significant way, although they are composed one after the other.

The name comes from later musicologists, and the meaning in Italian isn’t really about popularity, even though these three operas are the most played of Verdi’s operas. Instead, it means more of common folks and popular culture. These three titles are not only about Kings, Dukes, and nobles. Instead, the main character is a prostitute, a clown, and in this case a Gypsy.

Premiere – January 19, 1853, Teatro Apollo, Rome, Italy

Premiere – January 19, 1853, Teatro Apollo, Rome, Italy

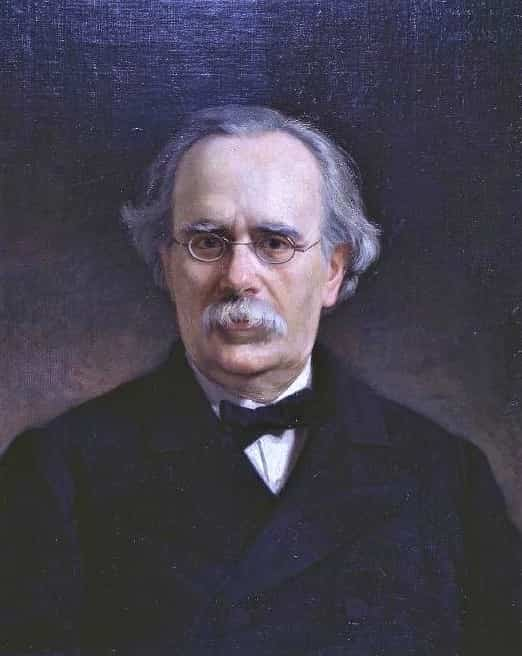

Composer – Giuseppe Verdi

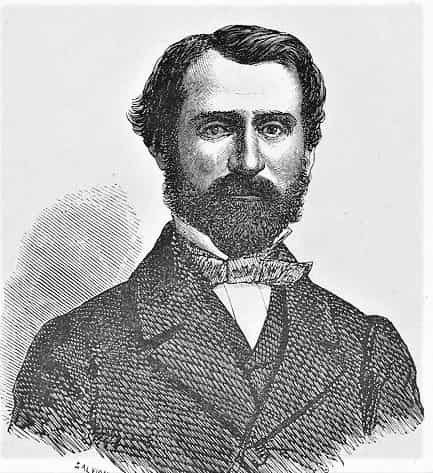

Librettist – Salvadore Cammarano (Leone Emanuele Bardare)

Running Time – Approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes, plus Intervals

Four Acts

There is no overture.

Act 1 – 30 minutes

Act 2 – 45 minutes

Act 3 – 25 minutes

Act 4 – 40 minutes

In Italian

Main characters

Il Conte di Luna/Count of Luna, Young nobleman from Aragon: Lyric-Dramatic Baritone.

Leonora, Lady-in-waiting of the Princess of Aragon: Lyric Soprano.

Azucena, Gypsy woman from Biscay: Dramatic Mezzosoprano (contralto)

Manrico, The troubadour, Officer of Count Urgel. Also the presumed son of Azucena: Lyric-Dramatic Tenor. More about the voice of Manrico here.

Ferrando, Captain of the guard of Conte di Luna: Bass.

Based on the play El Trovador by Antonio García Gutiérrez.

Download this short Pdf-guide. Print it, fold it, and keep it in your pocket as a help when you’re at the Opera. Please keep your phone turned off when inside the theater.

The absurd story of Il Trovatore.

Many operas by Giuseppe Verdi can be a bit awkward to grasp for the average listener. His stories are often complex and sometimes challenging to follow… Or you need a background of the historical events leading up to the actual situation. Il Trovatore is, I would say, some sort of record from that point of view.

But apart from being difficult to follow, it is also in many parts, completely absurd. Some of the characters behave in very strange ways, and for a modern listener, many choices made both by the composer, and the characters within the opera are right out stupid.

Having said all that, Il Trovatore is an awesome opera. The music is beautiful and in some instances unique even for Verdi… And even the strange and sometimes ludicrous behavior of some of the characters can be entertaining.

So if you ever wanted to be prepared before going to the opera, this time the preparation should be even more thorough. Especially the background story, as told by Ferrando in the opening of the opera, is important.

Background – The Opera Il Trovatore is set in…

Biscay and Aragon, Spain.

Time: The 15th century.

The background is a historical fact. When Martin of Aragon, King of Aragon, Valencia, Sardinia, Corsica, and Sicily died in 1410, he left no legitimate descendant to the throne. His children were all dead. Instead, for two years, Aragon was without a regent. At least five contenders for the throne came forward, one of which was the Count of Luna, the one in the opera. His baptism name was Ferdinand.

Plot

First Act – The Duel.

The guard room in the castle of Luna outside Zaragoza.

The opera opens up with a group of soldiers guarding while the Count of Luna walks restlessly below Leonora’s windows. The old captain, Ferrando, tells a story about the Count’s father and what happened many years previously. He sings for 10 minutes straight:

– Di due figli vivea padre beato… (His father had two sons…)

And the story is as follows:

The current Count had a brother. But he fell ill, and as customs were at the time, any misfortune could be blamed on the Gypsies (… Or any other minority group of suspicious origin, Jews, Muslims, people with darker skin than the average citizen, etc.). Count Luna’s father imprisoned a random Gypsy, accused her of causing the child’s disease, and executed her. With her last breath, while consumed by the flames, the Gypsy woman commanded her daughter to revenge her.

The daughter, who is in fact Azucena, somehow managed to grab the child (the Count’s brother) and throw it on the same stake as the mother. And although the burnt bones of a child were found in the ashes of the pyre, the father refused to believe his son’s death. He told his firstborn, the present Count of Luna, to seek Azucena and revenge on his brother. Soon after, he died of a broken heart.

Garden in the palace of the princess.

Leonora sings:

Leonora sings:

– Tacea la notte placida /… Di tale amor. (The peaceful night lay silent… A love that words can scarcely describe.)

That is 8 minutes of demanding singing right off the bat.

She tells her maid, Inez, about the love of her young life. A mysterious young nobleman. She saw him at the tourney, some time ago, but lost track of him again. Now he has come back, and every night he sings outside her chambers…

– Verses, beseeching and humble, like a man praying to God…

The voice belongs to the Troubadour, who is Manrico. He is very much in love with Leonora. Obviously, the Count is also in love with her, and he knows about the mysterious singer. That is the reason why he roams the premises at night. He tries to catch his rival.

The two women leaves, and the Count approaches. He’s just about to follow Leonora when he hears Manrico’s voice…

– Deserto sulla terra… (All alone on the earth, at war with his evil fate…)

No, he doesn’t really sing for her. The serenade is all about himself, and how awesome he is. From there, what follows is one of the most absurd parts of the plot.

Because Leonora comes down into the garden again searching for Manrico, but she somehow misses him and declares her love for the Count instead. It is very dark among the trees. Manrico sees this and interprets the situation as Leonora’s fault…

– Infida! (Treacherous!)

He and the Count then start quarreling. Manrico tells him his name and reveals that he is actually from the rival clan, the Urgels (Another contender for the thrown). They draw their swords and in the middle, Leonora tries to do something noble, and the only noble thing she can think of is sacrifice. She urges the Count:

– So let your fury fall on the evil girl who offended you… Plunge your sword into this heart!

In the end, there is actually no duel at all. The two combatants just leave, while Leonora faints, suitable for a 15th-century lady. (Notice that no one of her lovers stays behind to check up on her…)

Disclaimer. Some directors have Manrico sort of winning or something… Verdi writes “The two rivals walk away with drawn swords” though.

Second Act – The Gypsy.

A gypsies’ camp on a mountain slope in Biscay.

Now there are two important pieces. First, the Gypsies sing:

– Vedi le fosche notturne spoglie…

… which is a beautiful and particular Verdi chorus. It has a distinct 1800 Gypsy feel to it with an anvil and hammer on stage beating the rhythm. After that Azucena sings her most famous aria:

– Stride la vampa… (… The flame crackles! The victim arrives, dressed in black, disheveled, barefoot…)

If you listen closely, you note that the excellent Dolora Zajick actually does the trills as Verdi wrote them.

And slowly she reveals the terrible story.

After the aria, the Gypsies all leave and only Manrico, her son, remains. He asks her about the past and she continues with the tale in the form of a second aria:

– Condotta ell’era in ceppi

Slowly and with ever stronger emotions she goes on to tell how she kidnaped the Count’s son. But when she had decided to throw him into the flames she had her own beloved offspring at her side. She grabbed the young Count but after the terrible deed, Luna’s child was still standing there, while her own son was gone.

– Ah! Mio figlio! Mio figlio! ( My son, my son!)

She had killed her own son. A blood-curdling development. Obviously, all this plants I seed of doubt within Manrico.

– I am not your son, them?

And The poor mother has to spend quite some time trying to convince him how much she loves him and that he truly is her son. Which, as you by now, should know is untrue.

Then there is another famous piece. Namely the duet:

– Mal reggendo all’aspro assalto…

In it, Manrico explains the strange sensation he had when he was about to plunge his sword into the Count. (… And this is maybe why sometimes the duel that finishes the first act has Manrico as a winner.) Of course, it’s because they are actually brothers. Azucena makes him swear to kill him the next time though.

A messenger comes in announcing that the Urgels have captured Luna’s castle. But more importantly… Leonora (who throughout the opera continuously acts without any patience at all…) somehow has gotten the idea that Manrico is dead, and has decided to hastily become a nun. So Manrico must ride to Zaragoza to try to stop her.

The cloister.

The Count, Ferrando, and a few loyal men are there to get Leonora out of the Monastery. Count of Luna sings his big aria:

– Il balen del suo sorriso… (The flicker of her smile is brighter than a star’s ray!)

… which is in fact much more loving and tender than what Manrico manages to put forward anywhere within the whole opera.

The men silently sneak in with the intention to snatch Leonora before she has pronounced the vows. When he jumps forth in front of his beloved, Leonora isn’t all that impressed. But when Manrico arrives the minute after, she immediately forgets all about becoming a nun. Manrico has returned from the shadows, and now once again faces the Count and his men.

This time the Urgels win, and Count of Luna is defeated. There is still no duel between the two rivals though. And if you wanted to see any real fighting, chances are you will be disappointed. The act finishes with a lot of confusion but no real conclusion. Between the second and third acts, Manrico and the Urgels take the castle though, and Count of Luna is thrown out.

Third Act – The Gypsy’s son.

Count of Luna’s military camp.

Count of Luna is preparing the assault on the castle to take it back. And, of course, to kill Manrico.

Ferrando gives notice that the men have caught a Gypsy woman sneaking around in the neighborhood. When she’s brought before the Count, he interrogates her:

– Where are you from?

– Biscay.

– Have you lived there for long?

– Yes, a long time.

The exact answers she shouldn’t have given. She goes ahead and names Manrico, her son, and she has definitely managed to make a desperate situation completely hopeless. When Ferrando, who has been serving the Lunas for a long time, sees her, he can definitely confirm that this is the Gypsy that killed the Count’s brother.

Let’s reflect for a moment. The Count had one reason to hate Manrico, the fact that they both love Leonora and that she seems to prefer Manrico. Then he learned that Manrico is an officer in the competing clan… The Urgels. Now this Gypsy who killed his brother confesses that Manrico is her son.

The scene finishes with a beautiful uptempo ensemble with the Count, Azucena, Ferrando, and all the men:

– Deh! rallentate, o barbari…

Inside the castle of Luna… Now held by Manrico and his men.

Manrico and his men are waiting for an inevitable attack at dawn. Secretly, Manrico and Leonora are planning to wed. Manrico sings:

– Ah sì, ben mio, coll’essere…

This is a love song to Leonora, or as close to declared love as Manrico ever gets. He is mostly singing about his own death though…

Ruiz, Manrico’s second, rushes in before the ceremony, and tells him about Azucena:

– The Gypsy… They have already lightened the stake…

And of course, Manrico abandons Leonora and hastes away to save his mother. But before doing so he sings the absolute highlight of the evening:

– Di quella pira… (The blaze of the pyre enflames all of my being!)

And if it’s done right, the tenor should bring down the house.

This is from Barcellona 1983. Franco Bonisolli, who was a fantastic Manrico, for some reason cracked the high C. He went out but came back and delivered it in a perfect manner a Capella.

Fourth Act – The Execution.

A dark wing of the castle.

The attempt to free Azucena didn’t go well, and Manrico was captured and imprisoned.

Ruiz and Leonora are hiding in the shadows. She has a plan to save her lover, but it requires a sacrifice. She sings the beautiful but difficult aria:

– Timor di me? / D’amor sull’ali rosee…

This too can be a show-stopper if it’s done well.

The Monks pray for the condemned’s soul to be accepted into heaven. She hears Manrico singing out his love for her from the cell… Or at least, sort of. The two sing a sort of duet without seeing each other and without him knowing about Leonora’s presence.

The Count enters and Leonora reveals herself. She proposes a deal to save Manrico. The only deal a 1400s noble lady could ever do. She will marry the Count in exchange for Manrico’s freedom. But when he is distracted for a second, she takes a potion of hidden poison from her ring, and whispers:

– (You’ll have me… but as a cold and lifeless corpse.)

The prison cell.

Manrico tries to comfort Azucena, who is terrified by the thought of the flames. She is now facing the same fate as her mother. They sing a beautiful duet (Compare to the Alfredo-Violetta duet in the third act of La Traviata “Parigi, o cara…”):

– Ai nostri monti ritorneremo… (We’ll return to our mountains, and once again we’ll have peace…)

Azucena falls asleep. And then Leonora enters with the good news that Manrico is free. But instead of heading for the door, Manrico gets furious because he understands what Leonora’s sacrifice consists of.

– Ha quest’infame l’amor venduto… Venduto un core che mio giurò!

… And he continues to insult her in every way until she practically starts dying. Because again she was too impatient. She took the poison a fraction too soon and now her life spark is fading. at that point, Manrico changes attitude, and suddenly to him, she is an angel.

Here, there’s also a very strange trio. Manrico and Leonora with the sleeping Azucena cutting in with her dreams.

The Count enters and he is not happy with the outcome. His bride is dead, and so the deal is off. He orders Manrico to his execution. Azucena finally wakes up just to see Manrico being dragged away. When the headsman has completed his task, her only comment is:

– Egl’era tuo fratello! (He was your brother… Mother, you are avenged!!!)

What to look out for.

First Act

1 min – All’erta! All’erta! Ferrando sings the long tale of the background story. There should be two choruses, but most productions have only one.

14 minutes – Tacea la notte placida. Leonora’s first aria. Difficult and long.

23 minutes – Deserto sulla terra. Manrico’s first aria, off stage.

25 minutes – Leonora comes out and embraces the wrong man.

27 minutes – Di geloso amor sprezzato. Count of Luna begins the final trio.

30 minutes – At curtain-close, check if the duel has any decisive outcome…

Second Act

Curtain up – Vedi! le fosche notturne spoglie… Famous chorus piece.

3 minutes – Stride la vampa. Azucenas first aria.

18 minutes – Mal reggendo all’aspro assalto… Manrico and Azucena’s duet.

26 minutes – Il balen del suo sorriso… Count of Luna’s big aria.

32 minutes – After the soldiers enter, the Count sings the cabaletta… Per me ora fatale.

40 minutes – E deggio e posso crederlo? The final trio with Leonora, Manrico, and Luna with a lot of soldiers on stage.

Third Act

5 minutes – Azucena is captured and interrogated.

10 minutes – Deh! rallentate o barbari. Duet and chorus, Luna and Azucena.

16 minutes – Ah sì, ben mio, coll’essere… Manrico’s second aria.

22 minutes – Di quella pira. Manrico’s third and most famous aria.

Fourth Act

3 minutes – D’amor sull’ali rosee. Leonora sings of lost love and sacrifice…

19 minutes – Vivrà! Contende il giubilo. A scizzofrenic duet where Leonora sings to Manrico while the Count expresses his love for Leonora.

29 minutes – Ai nostri monti ritorneremo. Last duet, Manrico and Azucena.

31 minutes – Leonora enters and Manrico starts offending her.

37 minutes – Leonora starts dying and Manrico stops offending her.

40 minutes – Egl’era tuo fratello! Azucena’s last line… That was your brother, Mother you are avenged!

Something about the opera Il Trovatore – The Troubadour.

Giuseppe Verdi wrote his opera with Antonio García Gutiérrez’ El Trovador as a base. Verdi’s future wife Giuseppa Strepponi loved the Spanish novel and she actually translated it into Italian. Verdi too felt a special attraction to the story. The Maestro was by this point a highly acclaimed and celebrated composer and his financial situation was such that he needed no commission to start writing. He was his own master.

The librettist chosen for his new masterpiece was the very established Salvadore Cammarano. Though artistically very able, he didn’t always get along with the composer. Cammarano was a traditionalist, while Verdi wanted to venture outside the conventions. Unfortunately, Cammarano died in 1852 before his work was finished. Verdi chose the young Leone Emanuele Bardare as his successor. Most musicologists agree that his contribution enhanced the value of the opera.

So, although Verdi wanted to explore new expressions, Il Trovatore is rather traditional in its form. The choruses, the two-part arias, the cabalettas are all evident throughout. The spicy stuff is more in the orchestration, where Verdi had more freedom. One such example is the Gypsy chorus of the second act.

Verdi initially wanted Azucena to be the main character. The intricate and troubled mindset of the woman is undoubtedly fascinating. It could be that it just wouldn’t attract as much attention. A tenor-soprano love story was more selling. At least until Carmen premiered some twenty years later…

Something about the voices.

Someone once said that for Il Trovatore you need not one, not two, but four of the best voices in the world, one of each major voice type. I do not necessarily agree. The difficulty consists in singing in a traditional and somewhat old style. As said before, Verdi’s vocal score is old school. The two-part writing with a final cabaletta/stretta can be uncomfortable.

One example is Stride la Vampa, Azucena’s first aria. It has trills every two or three bars. That, together with the fast movement of the score makes it difficult for one who’s not used to that sort of technique, and often the mezzo-soprano just omits the trill. Like everything in this world though, if you know how to do it, it’s not hard.

The most famous aria of the opera is without doubt Manrico’s aria in the third act Di Quella Pira. It is not an easy piece. It has two high C, one shorter in the middle, and one very long at the end. It is sometimes regarded as a championship aria. The one who holds the final C the longest wins.

But again, it is not all that difficult if you have a decent Lyric-Dramatic tenor. But if the singer is a normal Lyric tenor (…Or even a light Lyric tenor, as we’ve seen in later years), the fast movements, the powerful output, and the high tessitura makes it burdensome. What happens is that a Lyric tenor would transpose it down half a tone. So paradoxically, with a lighter voice, you will hear it lower.

Or you can do as Placido Domingo did in his later performances, just cut out the C:s (Or B flats in his case). They are actually not written by Verdi, and Domingo insisted on being faithful to the original.

Il Trovatore – A playground for wacky people.

You can’t deny it. Of the four main characters, only Conte di Luna seems to have something that actually works behind his forehead.

Manrico is an impulsive guy, a fighter, a soldier. But he doesn’t seem to understand much of love or of life in general. His treatment of Leonora makes one wonder how on earth she puts up with him. When Azucena practically confesses to not being his mother and then takes it all back, Manrico’s response is… “Ok, whatever”. He is one of those classmates who copies all of your homework, and then gets a better grade on the test.

Leonora is an oppressed and abused woman who seems to be fine with being oppressed and abused. Manrico never brings her flowers or gifts or anything that could resemble kindness. All he does is insult her and run from here to there to fight the count. In the last scene when Leonora has sacrificed her life for him, he continues accusing her of infidelity… And instead of telling him to go to hell, all she can say is:

– Oh, how your wrath blinds you!

I mean, get real, girl…Take the Count instead. At least he is alive…

… And don’t let me get into the true champion of brainless… Azucena.

Verdi is of course not the only one to blame here. The novel wasn’t his. But for some reason, he chose it and kept the story as we see it in the opera. And maybe, after all, that was a conscious choice.

Yep, it’s a stupid people’s playground. From the spectator’s point of view, that doesn’t have to be a negative factor, though. On the contrary, I believe the absurd reactions, and unexpected behaviors make the opera even more enjoyable. Instead of a dusty old tale of medieval kings and queens, we have a lot of strange and extraordinary happenings. It is simply more surprising and interesting this way.

Download this short Pdf-guide. Print it, fold it, and keep it in your pocket as a help when you’re at the Opera. Please keep your phone turned off when inside the theater.