Pagliacci

Pagliacci is Leoncavallo’s most famous opera. The composer stroke big at his very first attempt. Just think that his second most performed opera is La Bohème. Yes, the same story as Puccini’s masterpiece, but Leoncavallo’s opera about the French bohemians isn’t among the top 100 today.

But Pagliacci deffenitely is. And it is very often combined with another one-act opera to make up a full evening performance. For many years the standard combination was with Cavalleria Rusticana by Mascagni. That program was so common that the English speaking world has a label for it… Cav/Pag.

Lately, many theaters have started experimenting with other one-act operas or ballets together with either of the two operas.

Premiere – May 21, 1892, Teatro Dal Verme, Milan, Italy.

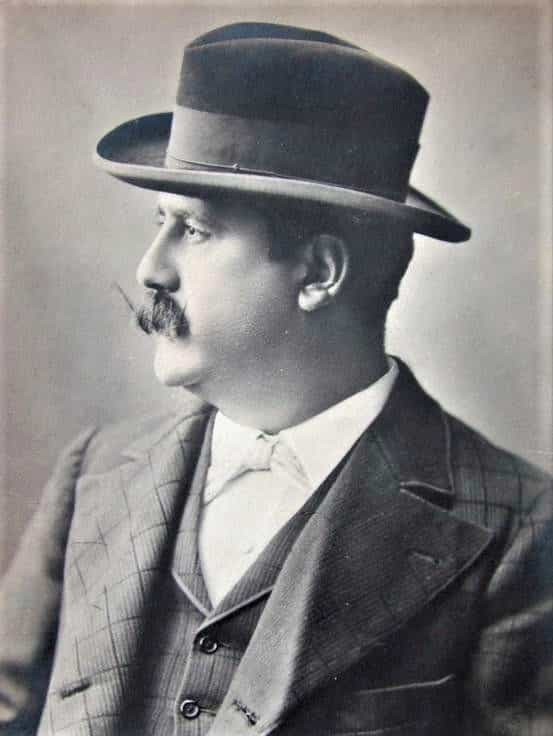

Composer – Ruggero Leoncavallo

Librettist – Ruggero Leoncavallo

Running Time – 1 hour and 15 minutes.

Two Acts

Overture/Prologue 8 minutes.

Act 1 – 40 minutes.

Interlude – 4 minutes

Act 2 – 23 minutes.

In Italian

Main characters

Canio/Pagliaccio – The director of the small, traveling theater company. Lyric-Dramatic tenor.

Nedda/Colombina – Canio’s wife and co-actor: Lyric soprano.

Tonio/Taddeo/The prologue – Actor, The fool: Lyric-Dramatic barytone.

Beppe/Harlequin – Actor: Lyric (Light lyric) tenor.

Silvio – Villager: Lyric barytone.

The opera is based on an actual murder case that involved Leoncavallo himself as a child.

Download this short Pdf-guide. Print it, fold it, and keep it in your pocket as a help when you’re at the Opera. Please keep your phone turned off when inside the theater.

The actual legal case that involved Leoncavallo.

The opera premiered in 1892 and the conductor was no less than the great Italian Maestro, Arturo Toscanini. He was only 25 years at the time and not yet as famous as he would later become, not even to the Milan audience. The success of the opera made waves in the operatic world and soon it was translated into other languages… French for example.

When it was set up in Paris, the French writer Catulle Mendès accused Leoncavallo of plagiarism. His own La Femme de Tabarin in fact has more or less the same story (… That he, in turn, had copied from the opera Tabarin by Émile Pessard).

Anyway, Leoncavallo defended himself saying that he had based his opera on a real event that happened when he was a child. The event he referred to was the murder of the composer’s tutor in the small town of Montalto Uffugo in southern Italy. Ruggero was only 8 at the time, and his father, Vincenzo Leoncavallo, who was a judge from Naples, convicted the two accomplices.

And this is what happened.

Pagliacci – The chronicle.

In 1865 the young employee at the Leoncavallo residence, Gaetano Scavello had an affair with a young girl who was engaged to another man by the name of Luigi D’Alessandro. One day Gaetano sees D’Alessandro’s younger brother coming out of the girl’s house, and he asks him what he’s been doing there. The boy doesn’t say anything so Gaetano beats him with a rod.

The next evening Luigi together with another of his brothers, a certain Giovanni, approach and stab Gaetano Scavello in the middle of the square. He dies in the hospital a short time thereafter, but he is able to communicate the names of the aggressors. That day a traveling theater company was playing, and the square was crowded, and thus it was easy for the perpetrators to get close to Gaetano, and then escape. They were both sentenced to prison and forced labor.

So, there was a murder and the cause was jealousy. The traveling theater was present but not directly involved. No one was married, but there was some sort of an engagement, at least on D’Alessandro’s part. The girl/wife wasn’t killed, and there is no record of any Tonio-type character.

It is close, but I would say that these kinds of tragic events happened, and happen frequently. Leoncavallo developed a plot that in no way needed these facts. He was probably inspired by them, but the story in the opera is all his own… (Or maybe it is Catulle Mendès’). Though we should recognize that Leoncavallo inserts something of the original event already in the Prologue, as well as the time and place of the story.

Background – The opera Pagliacci is set in…

Montalto Uffugo in the region of Calabria, Italy.

The time period is 1865-1870. The time of year is at the feast of the assumption in mid-August.

Plot

Prologue

The opera starts with a short overture, after which Tonio steps up in front of the curtain. He presents himself as The Prologue, singing a famous aria, often performed as a stand-alone concert piece. In it, he makes a very important statement. The prologue in the old Comedia-dell Arte-tradition was a way to present the play and to assure the audience that although the style of the drama and the expression of the artists are dramatic, it’s all make-believe and not real… They are just acting. This Prologue instead says that it is, in fact, real, an image of what real life is like.

– Truth is his (the author’s) inspiration. Deep-embedded memories stirred one day within his heart…

He continues connecting his words with the famous tenor aria at the end of the first act, and with the underlying bottom line of the opera.

– For we (the artists) are men of flesh and bone, like you, breathing the same air of this orphan world.

First Act – On with the show! Begin!

In the middle of the square, the villagers are singing, drinking, and having a good time. It’s Ferragosto, and everybody is free. A newly arrived theater company presents their performance later that evening. Canio sings:

– Un grande spettacolo. A ventitré ore… (A great show. At eleven this evening.)

If you are observant, you should be able to notice a certain disturbance in the relationship between the actors. Canio shows an inviting face to the villagers, but with his colleagues, the feeling is a bit cruder. A young man in the crowd makes a harmless joke about Nedda and Tonio, and Canio darkens:

– Un tal gioco, credetemi… (Better not to play that game… Theater and life are not the same… I love my wife more than anything, and up there, when Pagliaccio surprises his wife with a lover, everybody claps their hands and cheers… In real life the story would have a very different ending.)

Nedda is of course very disturbed by Canio’s remarks.

The scene finishes with a beautiful, and innovative chorus:

– Din, don. Suona vespero…

Nedda’s issues.

Nedda alone sings:

– Qual fiamma avea nel guardo… Hui! Stridono Lassù.

A long and demanding aria for soprano. At the very beginning, we hear the love theme. But not the love between Canio and Nedda, because the young woman has another lover… A boy from the village whose name is Silvio. The second part of the aria is about the swallows in the sky, and in a much lighter tone:

– … Avid for air and splendor, let them pursue their journey… They too…

Tonio enters. He remained behind the others just to be with Nedda. Much like most men around her, he too is in love with her. He declares his feelings in the short melody:

Tonio enters. He remained behind the others just to be with Nedda. Much like most men around her, he too is in love with her. He declares his feelings in the short melody:

– So ben che lo scemo contorto son io… (I know that I am the twisted half-wit… But even so, I too dream. I too

know in my heart the pulsing of desire…)

Again Leoncavallo expresses his sad observations of the world.

But his clumsy and stupid advancements just make her laugh and ridicule him. When he gets physical, she finally defends herself by whipping him, and he swears to get back at her…

Tonio runs away, and finally, the handsome Silvio arrives. The two lovers declare their passion for each other. Silvio asks her to leave with him, and reluctantly she agrees. At midnight, after the show, they shall meet and flee together. Nedda tells him:

– A stanotte, e per sempre io sarò tua… (Tonight I shall be forever yours…)

It’s interesting how timeless Leoncavallo’s story is. Nedda is young and beautiful. She has been taken care of by Canio, who gave her a home and a family. But now, although everybody wants her, and maybe just because of that, she is completely abandoned. It seems that anywhere she chooses to go, the outcome depends on the men surrounding her. Her future isn’t hers but is in the hands of those men, blinded by their jealousy.

Canio’s issues.

But Tonio has seen them, and he’s gone to fetch Canio. And the husband jumps out furious and ready to commit the ultimate crime. Silvio escapes and Canio do not see his face. He then turns to Nedda, and with increasing rage, he demands the name of her lover. With his knife raised, he comes at her.

– Il nome, il nome, non tardare, o donna! (The name, the name, woman… don’t waste time!)

– Non lo dirò giammai! (I’ll never tell you!)

Beppe runs in and practically saves Nedda’s life, trying to calm Canio.

– People are leaving the church and coming for the show… She’ll tell you later… Now hurry, get dressed!

And we have arrived at the point many of us have been waiting for. Canio’s aria:

– Recitar… Vesti la giubba… (Play, perform, while racked with grief… Put on the costume, powder your face. The audience has paid and they want to laugh. Change your tears into clowning, and your pain into a grimace… Laugh, Pagliaccio, at your shattered love!)

It is short but extremely powerful. The artistic conflict that so many musicians, singers, and actors, live. In some way, you sell yourself, but not you in the way you really are. The audience buys an image of you, and that’s what you have to give them.

Interlude.

Second Act – The theater in the theater.

This is an often-used concept. You have the actors set up a play inside the play. But in the case of Pagliacci, it couldn’t be more on spot. The Comedia dell’Arte production includes exactly the same situation as just happened but in a comedy context. So Canio is playing Pagliaccio whose wife Colombina is unfaithful with Harlequin.

A solo trumpet invites the town to the show. And the villagers show up with another wonderful chorus:

– Presto, affrettiamoci… (Come on, let’s hurry!)

There’s a small stage and the audience sits down to watch the show.

Bebbe/Harlequin sings a serenade for Columbina:

– Ah! Colombina, il tenero Fido Arlecchin…

The comedy proceeds with Harlequin giving Colombina a drug to put into Pagliaccio’s drink. Colombina answers:

– A stanotte, e per sempre io sarò tua… (Tonight I shall be forever yours…)

The exact same phrase Nedda said to Silvio earlier. And Canio enters as Pagliaccio but it is soon obvious that he can’t separate the play from the previous events. Within the play, he should ask Colombina about Harlequin. But in his head, it’s all about Nedda’s lover and who he is. When Colombina desperately tries to push him back into his part, he definitely leaves all role-playing when exclaiming:

– No Pagliaccio non son… ( No, I’m not Pagliaccio… Although my face is white… The heart that bleeds wants blood to wash away the shame!)

An equally powerful aria and maybe even more distressing. In fact to such a degree that the audience gives him a hand of applause thinking it was a part of the play.

But the inevitable tragic ending of the story is approaching. Canio wants the name, and when Nedda refuses to tell him things go terribly wrong.

In Leoncavallo’s score, it is Tonio who speaks the last phrase, but modern productions often have Canio saying:

– La commedia è finita! (The comedy is ended!)

What to look out for.

First act.

Before curtain-up – Si può? The Prologue, sung by Tonio.

3 minutes – Un grande spettacolo a ventitrè ore… Canio’s first aria.

5 minutes – A villager provokes Canio and he answers… Un tal gioco, credetemi.

9 minutes – Din don… Chorus.

9 minutes – Din don… Chorus.

12 minutes – Qual fiamma avea nel guardo… Nedda’s aria.

17 minutes – Tonio arrives.

21 minutes – Nedda strikes Tonio.

27 minutes – Tonio sees Silvio together with Nedda. He fetches Canio.

32 minutes – Canio arrives, and Silvio escapes.

35 minutes – Recitar… Vesti la giubba. Canio’s most famous aria.

Interlude.

Second act.

5 minutes – O Colombina, il tenero Fido Arlecchin… Beppe’s/Harlequin’s aria.

13 minutes – A stanotte… Nedda’s phrase to Harlequin that makes Canio snap.

16 minutes – No, Pagliaccio non son… Canio’s last, and most dramatic aria.

22 minutes – La commedia è finita… Check who pronounces the famous last phrase of the opera.

Caruso’s recording of Vesti la giubba.

Pagliaccio was a huge success from the get-go. The reason is of course that it is a brilliantly composed opera, with many wonderful and emotionally enchanting show-stoppers. Another reason could be Enrico Caruso’s recording of Ridi Pagliaccio…

The great tenor made several recordings of the aria, both with just piano accompaniment and with a full orchestra. The recording from March 17, 1907, made in New York, sold more than 1 million copies worldwide. A record at the time and even today a respectable number. That recording made Caruso a star far beyond the opera stage. It cemented him as the undisputed number-one tenor in the world. And it merged him somehow into the character of Canio/Pagliaccio.

Pagliacci is a Verismo opera.

As one of the best examples of Italian Verismo, Pagliacci not only tells a brutal, sad Verismo story. Also, the way the singing is laid out is typical for the style. The singing score, especially Canio’s two last arias, presents a spoken or almost spoken line. It imitates the tones of an excited speech or is pushed almost to the point of screaming. Vesti la giubba in the first part is broken up by forced laughter. In other points of the opera, there are exclamations of joy, relief, pain, fear, etc… With a very spontaneous and realistic effect.

In the most dramatic moments, the singing stops, and the pauses of silence create tension and give a strong expressive charge, e.g. the ending when Pagliaccio first enters on stage. Then, when Canio sees Silvio and realizes that he is the one, he utters the words Ah sei tu? (So, it’s you?), written as reciting without notes. Just as is the last phrase La commedia è finita!

A curiosity about the name.

The opera was initially entitled Il Pagliaccio (the clown), referring to Canio as the one single clown. The French baritone Victor Maurel played Tonio in the first setup of the opera. As he greatly assisted the composer, Leoncavallo couldn’t deny him being included in the title. So when the great baritone asked for a change, Leoncavallo said yes… And Il Pagliaccio (the clown) became Pagliacci (clowns), and thus included Tonio and the other characters as well.

Download this short Pdf-guide. Print it, fold it, and keep it in your pocket as a help when you’re at the Opera. Please keep your phone turned off when inside the theater.